Andrea's initial notes follow:

Azad, Owen, and I met at Mim’s on a warm, beautiful evening and had a lively, interesting discussion. (The next day, we learned we showed up a week early.)

In an email a few weeks ago, for people who wondered about the connection between the Epic of Gilgamesh and Armenian-ness, Leroy (actually Peter) said this: “While this isn't part of our mythology tradition, Ishtar (who plays an important role in the story) is the Mesopotamian goddess of love. Her husband was the god of fertility, known as Dumuzi but also called Tammuz, which you've probably heard of as Tamzara from Armenian weddings, because it's a dance people will do at the reception. That dance is a holdover from this pre-Christian era. There are other Armenian connections, but I think this one is pretty interesting.”

I did make the following comment: "And if you'd like a further connection of Gilgamesh with Armenians ...

A large number of cuneiform tablets containing the story of Gilgamesh have been found in the Hittite capital of Hattusa. They are in three languages: Hittite, Akkadian and Hurrian. The Hurrian kingdom was north of Mesopotamia and east of the Hittites, just south of Lake Van. From Wikipedia - "The present-day Armenians are an amalgam of the Indo-European groups with the Hurrians and Urartians."

So, if you're Armenian your 200th great grandfather or grandmother may have been reading stories of Gilgamesh to their children when they put them to bed at night."

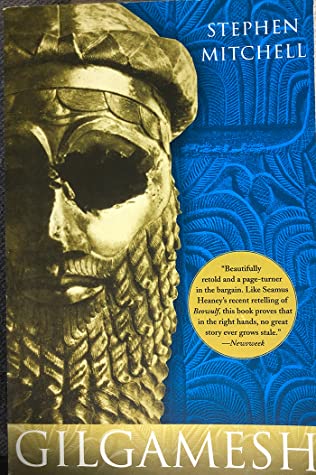

Stephen Mitchell’s Gilgamesh is an amalgamation of the three primary sources: fragments of five clay tablets written in Sumerian cuneiform, dating from 2100 BCE; eleven clay tablets in Old Babylonian (related to Akkadian) found in Nineveh, dating from 1700 BCE; and a version believed to have been written about 500 years later, a translation by a scholar priest named Sin-leqi-unninni. Mitchell relies heavily on Sin-lequi-unninni’s translation, while also incorporating some of the Sumerian poems. Mitchell acknowledges he has taken some liberties in his version, both omitting some of the repetition as well as including “added lines or short passages to bridge the gaps or clarify the story.” In his version, the epic story itself runs to 130 pages of double-spaced text. I found the language to be fresh, very readable, and quite fascinating. In addition, there is a lengthy introduction, copious footnotes, a glossary, and a bibliography.

A condensed summary of the epic, from Stephen Mitchell’s book:

Gilgamesh is king of Uruk, large, strong, all-powerful, intimidating to his subjects, who dare not defy his will. Gilgamesh has sexual relations with virgin brides before the brides and grooms have their wedding night. When the people of Uruk go to the god Anu to complain, Anu tells Aruru, mother of creation, to create a double for Gilgamesh, “his (Gilgamesh’s) second self.” Aruru then fashions Enkidu from clay. Enkidu is as physically large as Gilgmesh and equally strong. However, Enkidu is a human who lives like an animal in the wilderness, who has never been humanized or encountered civilization. A trapper becomes frightened at the sight of Enkidu, and his report travels all the way to Gilgamesh in Uruk. Gilgamesh sends the priestess Shamhat to the forest to find Enkidu and seduce him, then bring him to Uruk. She does this and in the process, she imparts human characteristics to Enkidu. She tells Enkidu about Gilgamesh’s tyranny over his subjects, including his bedding virgin brides before their wedding night, and Enkidu becomes enraged. Shambat leads him to Uruk. When Gilgamesh and Enkidu meet, a physical contest takes place and the two men fight like “wild bulls.” After the fight ends with Gilgamesh pinning Enkidu to the ground, the two embrace, kiss, and became “true friends.” Gilgamesh is no longer the same old tyrant. Gilgamesh convinces Enkidu they need to go to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster Humbaba. Enkidu is initially reluctant and fearful, but Gilgamesh appeals to his bravery as emphasizes the prospect of his becoming a hero. The two go to the goddess Ninsun, who blesses them and prays for their success. They then travel 1000 miles to kill the monster Humbaba, a six week journey that they accomplish in three days and nights. Enkidu has unsettling dreams along the way and is frightened. They arrive at Humbaba’s den and charge him “like wild bulls.” The god Shamhash assists by sending hurricane-force winds from all four directions. Humbaba begs Gilgmesh and Enkidu for mercy, to no avail. Humbaba then threatens that if they kill him, Enkidu will die. At this, Gilgamesh wavers but Enkidu tells him to have courage. Gilgamesh puts his axe through Humbaba’s neck and they take his head back to Uruk. The great goddess now Ishtar wants to marry Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh, already married, refuses and Ishtar curses him. This leads to Gilgamesh and Enkidu killing the Bull of Heaven, further infuriating Ishtar. Enkidu has more unsettling dreams, now about his own death. He becomes sick and dies, leaving Gilgamesh in deep mourning and terrified of his own death. He assembles the craftsmen of Uruk to make a statue of Enkidu, heaps up valuables from his treasury to be buried with Enkidu, and makes offerings to the gods, including to the goddess Ishtar so she will welcome Enkidu and walk by his side in the underworld. Then he sets off on a journey to find Utnapishtim, the only man to have become immortal. Utnapishtim is proto-Noah: he built an ark to save himself, his family, and diverse animals from the Great Flood, and the gods gave both him and his wife immortality. Along the way, Gilgamesh encounters Shiduri, a woman who is a tavern keeper. She tells him he will never find eternal life, instead, he should enjoy his life and be happy with his abundance of blessings. Nevertheless, Gilgamesh is determined to cross the Waters of Death to find Utnapishtim. Only the ferryman Urshanabi, who is Utnapishtim’s boatman, is able to cross the Waters of Death. Believing Urshanabi will refuse to take him across, Gilgamesh smashes the Stone Men who are the guides for the boat, then meets Urshanabi. Urshanabi tells Gilgamesh to cut down 300 punting poles to take on the ferry, so they can push the ferry using each pole only once, then discard it, using up all 300 poles to get to their destination while also protecting their hands from coming into contact with the Waters of Death. Gilgamesh does this, they make the crossing, and he finds Utnapishtim on the opposite shore. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh he cannot tell him how to have eternal life. He points out how fortunate Gilgamesh is and scolds Gilgamesh that his mind is filled with dissatisfaction, worry, and fear. “And what have you achieved but to bring yourself one day nearer to the end of your days?” After a few more incidents and adventures in the story line, the boatman, Urshanabi, takes Gilgamesh back across the ocean, but not before Utnapishtim tells him the “secret of the gods” – a spiny bush that is the antidote to fear of death. Gilgamesh finds the plant underwater and takes it back to Uruk. Finally, he recognizes his good fortune to be king of the city to which “no city on earth can equal.”

(Now, back to the meeting of the 24th.) Peter started out by talking about reading multiple versions of the Gilgamesh epic. He and I also both recently read a novelization of the story by Robert Silverberg. We discussed the variations in the way different translations combined the different sources and ages of cuneiform tablets to put their versions together. Since he was doing a novelization, Silverberg took great leeway in his story. He held true to the general story line, but also modified it to meet the realities of the geography of that area.

Peter talked about the history of the area, how the Sumerians were replaced by the Akkadians, then by the Babylonians and then by the Assyrians. When the Akkadians moved in on the Sumerians, there ended up being cuneiform tablets buried in their abandoned cities using the same script but in each of the languages. That held true for following years, too. Later tablets were in the Babylonian language and then the slightly different Assyrian language. In Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite empire in central Anatolia, cuneiform tablets were found which used the same script as in Mesopotamia but were written in the Hittite, Akkadian and Hurrian languages.

Peter briefly talked about how the clay tablets were created, and how they were put in clay "envelopes" to provide secrecy when they were sent to other locations.

Tashina mentioned that she read about Gilgamesh in a high school history class and she had found her notes, which included a printout of one of the translations.

Peter talked about how the gods in the earlier days of Mesopotamia were not considered to be all powerful and all knowing, they made mistakes and tried to correct them.

We talked about Gilgamesh and Enkidu hesitating to kill Humbaba and having to challenge each other a couple of times before they actually did it. Francis noted the discussion of the Cedar trees of Lebanon in this part of the story.

We talked about how there were variations in the story between the ages of the tablets. We also talked about how the basis for the stories of Noah's ark and Methuselah appears in the Mesopotamian mythology contained in the clay tablets.

As always, we spent about half of the time at the meeting talking about everything except the book under discussion. It was just loud and echoing enough in Mim's that many times a discussion at one end of the table could not be heard at the other end.

Now on to the rest of Andrea's report from the previous meeting:

Owen will be a senior at Hamline University this fall and is majoring in English/Creative Writing. He read the Epic of Gilgamesh in an English course at Hamline, a class that surveyed world epic literature over a wide span of time. The version of the Gilgamesh epic he read was by Benjamin R. Foster, The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation, Analogues, Criticism (Norton, 2001). Azad and I read Stephen Mitchell’s Gilgamesh. Owen noted that the Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest written literature in the world, has a theme that is common to all early literary texts: the journey of a hero, who travels away from home, then returns home and learns that what he was searching for was there the whole time. Other famous hero journeys include those found in the Old Testament (the next written text after the Epic of Gilgamesh), the Bhagavad Gita, Beowulf, and Shakespeare. Owen said Foster’s version of the Gilgamesh epic has gaps in the story as well as a lot of repetition, reflecting the authenticity of the primary sources, which is different from Stephen Mitchell’s approach. For example, Owen recalled that Gilgamesh smashes stones when he arrives at the body of water he wishes to cross to find Utnapishtim, however Foster’s translation gives no explanation for why Gilgamesh smashes the stones. In the Mitchell version, the stones are actually “Stone Men” which Gilgamesh smashes out of fury, believing the ferryman will refuse to transport him across the ocean to find Utnapishtim. Another difference is in how Foster and Mitchell treat Shamhat.

Azad read Mitchell’s book three times and made many notes, which are attached. His favorite part was Shiduri’s (the tavern-keeper) speech to Gilgamesh, in which she tells Gilgamesh to be happy with all his blessings and counsels him how to live a good life. He pointed out the similarity between the friendship of Gilgamesh and Enkidu to the friendship between David and Jonathon in the Old Testament. He noted there are a number of similarities to the Bible as well as to Buddhist texts. Azad also noted how Mitchell treats Shamhat: she is a powerful, positive creative force, a Priestess of Ishtar from Uruk whose job it was to civilize Enkidu. Owen contrasted that with Foster, who called Shamhat a prostitute. I hope Azad will share his notes and realize he may prefer to wait until after next week’s discussion.

I was interested in the strong women in the epic, including the goddess Aruru, who creates Enkidu from clay; Shamhat, the priestess, whom Gilgamesh sends to the wilderness to seduce Enkidu, teach him how to be human, and take him to Uruk to meet Gilgamesh; Ninsun, the goddess who blesses and prays for Gilgamesh and Enkidu before they venture into the Cedar Wood to kill Humbaba; and Shiduri, the woman who is a tavern-keeper, who tells Gilgamesh where to find the ferryman, and makes the beautiful wise speech telling Gilgamesh how to be happy and live a good life. Utnapishtim’s (proto-Noah) wife (unnamed), who like Utnapishtim has also been made immortal after the Great Flood, prompts Utnapishtim to tell Gilgamesh the secret of the gods, that the spiny plant will erase the fear of death. Ishtar, the goddess of heaven, becomes Enkidu’s protectress in the underworld.

Azad recounted the legend, from Armenian mythology, of Queen Anahit and Ara, how Anahit battled to marry Ara and he refused, a parallel to Ishtar’s desire to marry Gilgamesh.

It was such a pleasure to meet Owen and gain his insight into the Epic of Gilgamesh as well as learn how it is the first recorded epic hero journey in a genre that is foundational to world literature. Thank you, Owen, for attending the meeting. I hope you are able to meet with us again, as your time allows. (Note: Owen and I are both one quarter Armenian and we both have the last name Johnson.)

(Back to the end of the 24th meeting, again). There will not be book club meetings in July or August. For September, the proposal is to read "My Road to Home" by Vartan Gregorian.

Have a good summer and I hope to see you in September.

Leroy

ACOM Book Club June Meeting 2021

The ACOM Book Club met on Thursday, June 24, 2021, at Mim's restaurant on Cleveland Avenue in St. Paul. Attending this month were Cynthia, Kass, Peter, Francis, Tashina, Al and me. We attempted to provide a Zoom link for remote users to join in, but it didn't prove usefully workable. (Workably useful?) Andrea, Margaret and Joan made the attempt, but left after just a few minutes.

The book for this month was "Gilgamesh: A New English Version" by Stephen Mitchell.

Due to a miscommunication, Andrea and Azad met at Mim's a week earlier, along with Azad's grandson, Owen, who will be a senior at Hamline University this fall. Andrea wrote up a set of notes for their meeting which covered the book so well that I will intermix them with my notes. Andrea's notes will appear in blue. (Well, that worked in Thunderbird, but not in Facebook. Look for text hints instead.)